Winchelsea has a long and illustrious history. It originally began as an Old Saxon fishing town sometime around 800AD. It subsequently became a major port of the region. The name Winchelsea is integral to gaining an understanding this tiny town in Sussex. The suffix Chelsea is rooted in the Saxon word chesil, which refers to a shingle beach or embankment. The prefix Win on the other hand has been derived from the colloquial word qwent and refers to the marshland behind the town.

A wide shallow bay called the Camber was formed by the estuaries of the Rivers Brede, Rother and Tillingham and was situated behind the great shingle bank on which Old Winchelsea was perched. It provided a large tidal anchorage sheltered from the sea and ships would anchor stem-to-stern all along the channels and creeks. This would help them restock for supplies and get some rest before they move on for the rest of their journey.

The first documentary evidence for the existence of Old Winchelsea might be present in the Domesday Book (1086), which contained one of the earliest descriptions of present day Rye and Winchelsea.

An Ancient Town

Old Winchelsea rapidly developed into a major port and was soon recruited into the Confederation of Cinque Ports (pronounced ‘sink’). This was a friendly alliance of Sussex and Kent ports that was formed in Saxon times to provide ships and men to the Crown in time of war- up to 56 ships and men for up to 15 days a year. Merchant vessels of the time could be readily converted to warships. This could be done with the erection of castles on the forecastle and stern and was done regularly in times of need. In exchange for this ship service, the ports received various privileges. They could have their own courts, were given exemption from many royal taxes, gained the right to tax goods passing through their ports, and the right to wrecks and salvage.

By 1190, the status of Winchelsea and Rye in the Cinque Ports Confederation had been elevated to the Two Ancient Towns which means worthy of veneration, equivalent in standing and stature to the original five Head Ports. That was kind of a big deal back then.

Power And Wealth

By the time of the year 1204, Old Winchelsea was a prosperous port town. In fact, it was second only to London and Southampton on the southeast coast and was said to be considerably more important than Rye. We can see this in the kind of taxes that were paid- Winchelsea paid £62 in tax, compared to Rye’s £11 and Dover’s £32. That’s a huge difference even in those times.

Unlike other ports, Winchelsea did not serve a large land mass and thus the town’s fortunes therefore depended largely, on the sea. This was not easy for the locals and they had to go through a lot of struggles because of this. It was not all doom and gloom though. The foundation of Winchelsea’s prosperity was its original raison d’être, and main form of employment, fishing. Fish was a crucial element in the medieval diet. It was easy to procure and healthy and was rich in protein. Even in 1267, almost half of the town’s revenues were derived from that source.

Old Winchelsea also provided a haven to ships passing up and down the Channel. This helped trade flourish in the region. Alternate revenues were also generated, due to the influx of people, which would come and stay for a night or two in the port town. It also became the main port of embarkation for pilgrims going to the shrine of Santiago de Compostella. It had the benefit of becoming a regional centre for overseas trade with France, particularly with Flanders, Normandy and Gascony.

Winchelsea’s trade was mainly in bulk commodities. This mainly consisted of imports of iron, wine, salt, fish and foodstuffs. Exports were mainly of wood, fuel and fish. The trading of wine, not least from Gascony, was an especially important source of wealth for the town. New Winchelsea was one of the ten major wine ports in England in the first half of the 14th century. This contributed further to the flourishing trade.

Fishing and trade fostered various ancillary industries such as shipbuilding and repair. They were also helped by their proximity to the forests of the Weald. Wood was easily accessible and that made life a lot easier. These activities helped hugely in generating the ships and skilled manpower that was later harnessed for the war. It was not surprising that Old Winchelsea went on to house royal dockyards. In the wars with France that followed the loss of Normandy in 1204 and the subsequent French attacks on English possessions in Gascony and Acquitaine, Winchelsea was a major source of ships and men for the Crown. Winchelsea unsurprisingly provided more ships and men than any other English port during the 13th century. The harbour also made Winchelsea a major assembly point for English naval forces that needed to port.

Piracy

A lucrative sideline for Winchelsea’s mariners was privateering in wartime against foreign ships, and piracy in peacetime against both foreign and other English ships. This lends an interesting addition to the town’s already rich history. Privateering was a legitimate activity and thus the Crown took one-fifth of the booty that was garnered. Piracy was most definitely not, but it was difficult for the Crown to stop this activity. It was the same ‘pirates’ that provided much of the navy in times of war.

A lucrative sideline for Winchelsea’s mariners was privateering in wartime against foreign ships, and piracy in peacetime against both foreign and other English ships. This lends an interesting addition to the town’s already rich history. Privateering was a legitimate activity and thus the Crown took one-fifth of the booty that was garnered. Piracy was most definitely not, but it was difficult for the Crown to stop this activity. It was the same ‘pirates’ that provided much of the navy in times of war.

The piratical activities of the men of Winchelsea were often outrageous and have many tales attached to them. In 1290, when the Jews were expelled from England, Winchelsea ships attacked and robbed them in mid-Channel and stranded one party on a sandbank to drown as the tide submerged it. Not very pretty, but what do you expect from pirates after all? In 1321, ships from Winchelsea attacked Southampton. The piratical reputation of the men of Winchelsea was such that legend has it, that hatchets would be held up to ships entering western Channel ports from Winchelsea.

Piracy was not only the preserve of the criminal class. On the other hand, it was quite the opposite. Members of the illustrious Alard family (the first mayor of New Winchelsea was from this family) were frequently accused of piracy during the 13th and 14th centuries.

Old Winchelsea Drowned (1233-1287)

The success of Old Winchelsea was shattered by the start, in 1233, of a prolonged period of exceptionally turbulent weather that lasted until 1288. A long series of severe storms accelerated the eastward longshore drift of shingle in the Channel and started to break up the shingle bank on which Old Winchelsea was built. It is ironic that it was these same forces that had created the shingle bank in the first place. From 1244, Winchelsea was receiving regular grants towards its sea defences. This was a development of great concern for the locals.

The success of Old Winchelsea was shattered by the start, in 1233, of a prolonged period of exceptionally turbulent weather that lasted until 1288. A long series of severe storms accelerated the eastward longshore drift of shingle in the Channel and started to break up the shingle bank on which Old Winchelsea was built. It is ironic that it was these same forces that had created the shingle bank in the first place. From 1244, Winchelsea was receiving regular grants towards its sea defences. This was a development of great concern for the locals.

The description of the storm of 1250 suggests that the shingle bank on which Old Winchelsea stood was been permanently breached. By 1258, tides were running as far inland as Appledore, a distance of close to 8 miles from Old Winchelsea; an unheard-of occurrence. By 1280, the town and its surroundings were for the most part submerged. In November 1281, Edward I issued instructions to his steward, Ralph of Sandwich, for the town to be transferred to an alternative site.

On 4 February 1287, it was recorded that the sea flooded so greatly that all the sea walls were broken down and almost all the lands were covered in water as far as Winchelsea”. The unfortunate little town of Broomhill was swept away. The storm also appeared to have finished off what was left of Old Winchelsea, although its ruins were still visible at low tide for another five years. After this, the town seems to have disappeared from the pages of history.

The Foundation Of The New Town (1288-94)

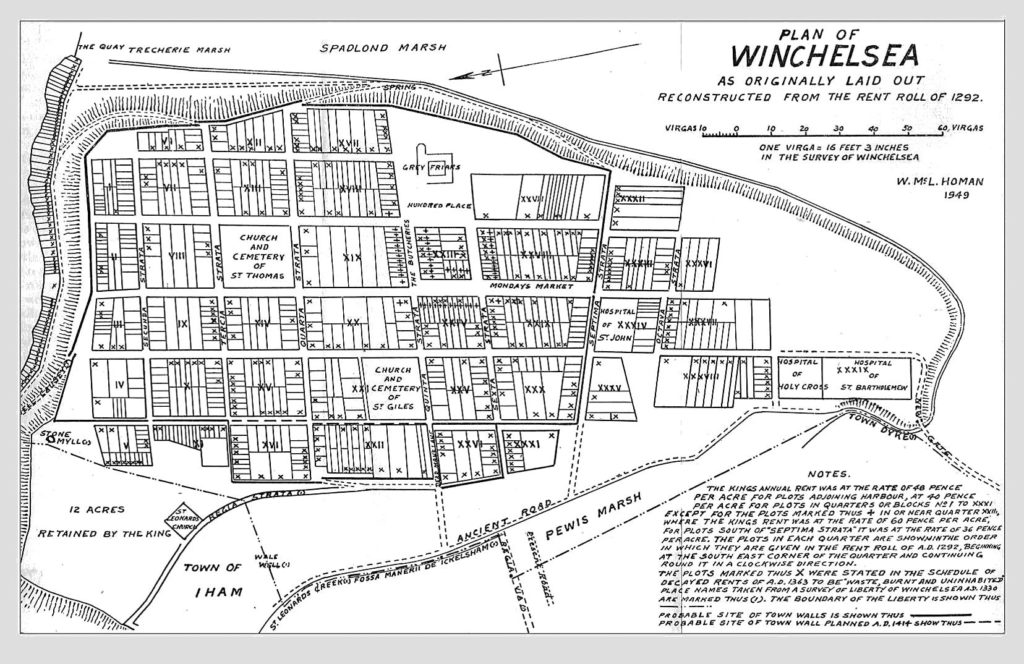

The site chosen for New Winchelsea was hill of Iham. This was located inland from Old Winchelsea, about 3 miles to the northwest of the old town. Thus, New Winchelsea was a little different from its predecessor. It was a river port rather than a coastal port like Old Winchelsea.

July 1288 is considered the date of the formal foundation of New Winchelsea, although many people also look to 1292, when the first rent roll was drawn up (residents paid ground rent to the Crown from 1295 after a seven-year grace period) as the date of foundation instead.

A Town Planned

New Winchelsea was not the first planned town in medieval England; these began all the way back in the 9th century. Nor was the grid pattern of its streets unusual or new. However, Winchelsea was unique in terms of the scale of the new town, the spaciousness of its streets, and the fact that it is still laid out as planned. It was unusual in having the streets numbered rather than named, something perpetuated in North American cities. This gave rise to the extraordinary local myth that the plan of New Winchelsea inspired the layout of New York.

The quarters were numbered. Quarter 1 was in the northeast corner of the town. The numbers then ran ‘horizontally’ along the top row of quarters to west as far as Quarter 5. The second row of quarters was similarly numbered from the east starting with Quarter 6, and so on.

A Town Planned: The Cellars Of Winchelsea

One of the most notable features of Winchelsea is the number of well-built vaulted stone cellars (its proper name is undercrofts). The number is matched or exceeded only in Southampton, Norwich and Chester. Some 33 of Winchelsea’s cellars are still accessible and the existence of another 18 medieval vaulted cellars is known

The cellars vary in size from 25 to 125 square metres, although the majority are in the range 30-50 square metres. The average cellar would hold over 120 hogsheads (6,300 gallons) of wine. Most of them are strong and well built. Some are quite elaborate, with decorative features such as chamfered ribs and corbelling, probably in Caen stone. Each cellar is entered by a wide flight of stairs from the street, and some have a rear entrance as well. Some cellars have windows, opening into stone-lined light wells leading up to street level.

The design of Winchelsea’s cellars and the quality of their construction points to commercial rather than domestic use. The principal commodity stored in the cellars is thought to be wine from Gascony. The current theory is that the cellars, at least those with windows providing natural light and with decorative features, were used as part retail wine shop and part wholesale wine sales area. That is the conclusion most experts came to.

A Town Planned: The Defences

The town of Winchelsea was surrounded by a ditch, wall and four main gates. Three of the gates are still standing today: Strand Gate, Ferry Gate, and New Gate. Work on the town defences probably started in 1295 and may have been completed by 1330, when the New Gate was built.

The Years Of Prosperity (1288-1350)

In the first decade following its foundation, New Winchelsea became prosperous and flourished economically. The fishing and trading activities that made the old town prosperous were successfully transferred to the new town. Its naval contribution to the Crown also continued to be head and shoulders above other English ports. For example, in the 1297 expedition to Gascony, Winchelsea provided a third of the force and many of the largest ships. It’s strength as a shipbuilding hub certainly didn’t hurt. One of its leading citizens and the first recorded mayor of Winchelsea, Gervase Alard junior, was appointed Admiral of the Western Fleet --- all the vessels in ship service from southern ports as far west as Cornwall.

As in Old Winchelsea, a large measure of the prosperity of the new town was based on the import of wine from Gascony. In 1306/07 alone, 737,000 gallons of wine was shipped into Winchelsea. It also continued as the main port of embarkation for pilgrims to Santiago de Compostella (they had 2,433 pilgrims in 1434 alone).

However, New Winchelsea’s most prosperous years were destined to be relatively short-lived.

The Years Of Decline (1350-1525)

The fortunes of Winchelsea started to decline in the latter half of the 14th century. By 1378, Winchelsea had been supplanted by Chichester as chief port of Sussex. By 1414, the southern and western suburbs had been abandoned. This signified the beginning of a downward spiral.

Winchelsea’s faced a severe decline in the 1300s and this has traditionally been attributed to attacks by the French and Castillians. It is claimed that the first such raid took place in 1326 and a quarter of the town was destroyed as a result. However, the town’s decline was probably down to a combination of factors. International conflict was certainly one of them.

Winchelsea’s faced a severe decline in the 1300s and this has traditionally been attributed to attacks by the French and Castillians. It is claimed that the first such raid took place in 1326 and a quarter of the town was destroyed as a result. However, the town’s decline was probably down to a combination of factors. International conflict was certainly one of them.

However, the most serious problem for New Winchelsea was the silting up of the harbour due to the infilling of the upper reaches of the River Brede to create new farmland. This reduced the flow of the river and its scouring effect on the harbour.

Economic forces were also at play in the decline of Winchelsea. The wine trade declined after 1337. By the middle of the 14th century, the focus of English trade was shifting away from Flanders, Normandy and Gascony to Spain and the Mediterranean. The advent of the Black Death in 1348 (it hit Winchelsea in 1349) made the struggle to overcome these problems that much harder.

However, the decline of Winchelsea should not be exaggerated. There is evidence that Winchelsea recovered rapidly from French and Spanish attacks. By 1388, the commercial core of Winchelsea had been re-occupied. Civic expenditure increased, and things were looking up again.